|

|---|

|

|---|

A rising post-90s generation is emerging as a strong engine of consumption, in one of four important new trends in the Chinese consumer landscape.

If you’re looking for evidence that Chinese consumers are confident, look no further than the one-day online-sales phenomenon known as Singles Day, which falls every year on November 11. Singles Day has morphed from being a day dedicated to lonely singles to becoming the largest e-shopping day globally. With an estimated $25 billion in sales, or over $1 billion in transactions per hour, Singles Day this year easily bested last year’s sales by close to 40 percent, and was larger than Black Friday and Cyber Monday in the United States combined.

Singles Day reinforces what we already know: Chinese consumers today are earning much more money and are spending that money on a wider variety of higher-quality and pricier goods and, increasingly, on services.

But only by digging deeper into the attitudes and behaviors of consumers can you see a more multifaceted set of consumer segments, each with unique characteristics that determine their shopping habits. This is what we’ve done with our latest survey of nearly 10,000 consumers aged 18 to 65 across 44 cities and seven rural villages and towns.

As in previous reports, we present four key trends that companies need to know to help them formulate their operational strategies in China. But this time, we reveal deeper, more meaningful layers of insight into what makes Chinese consumers tick today.

Understanding how they make the critical decisions that affect what they buy — and what they don’t — is vital for any company to succeed in this hotly contested market.

Official figures support what we saw on November 11. Since our last consumer survey, which we conducted in late 2015, consumer confidence has grown significantly in China to reach a ten-year high. On the back of this rise in confidence, consumers have been spending more on discretionary items.

But can this upward trajectory continue? There are several reasons to take a more cautious stance toward the future starting with the very high levels of debt that the Chinese economy overall and households are taking on. In 2017, the total leverage ratio in China hit 266 percent, the highest level it has ever reached. Meanwhile, household debt reached 50 percent, the highest it has been since the government started recording this figure, albeit still lower than developed countries. Debt levels aside, the real driver of spending is income growth, and this has slowed considerably, dropping from 10.1 percent in 2012 to 6.3 percent in 2016.

Chinese consumers are also running up against high real-estate costs, especially in tier-one cities, despite government measures to cool the market.

While these are all relatively short-term indicators, in the longer term, the rising costs of caring for elderly family members, particularly the healthcare expenses associated with such care, is set to become one of the biggest burdens on the budgets of Chinese consumers.

In the past few years we’ve noticed a substantial uptick in the number of Chinese consumers concerned about their health and the impact that diet, exercise, and the environment have on their quality of life (see sidebar “Fueling the fitness trend”). This year, our survey showed that 65 percent are seeking ways to lead a healthier lifestyle.

But this belies a more worrying trend. Millions of Chinese consumers have access to and can afford more types of food than ever before, and their bulging waistlines are evidence of this phenomenon.

Thirty percent of Chinese adults—roughly 320 million people—are overweight and about 6 percent obese.

The government has responded: in 2016 it announced the “Healthy China 2030 plan,” which pledged to promote initiatives geared toward diet, exercise, and access to healthcare services.

Our survey highlighted the early stages of shifting attitudes, especially toward healthy eating. Forty-one percent said “almost never” to eating unhealthy food. The instant-noodle and soda markets shrank by 7 percent and 2 percent respectively in 2016 compared with 2015. And, fast-food chains, already thought of as healthier than hole-in-the-wall restaurants and roadside stalls, continue to expand with healthier menu options

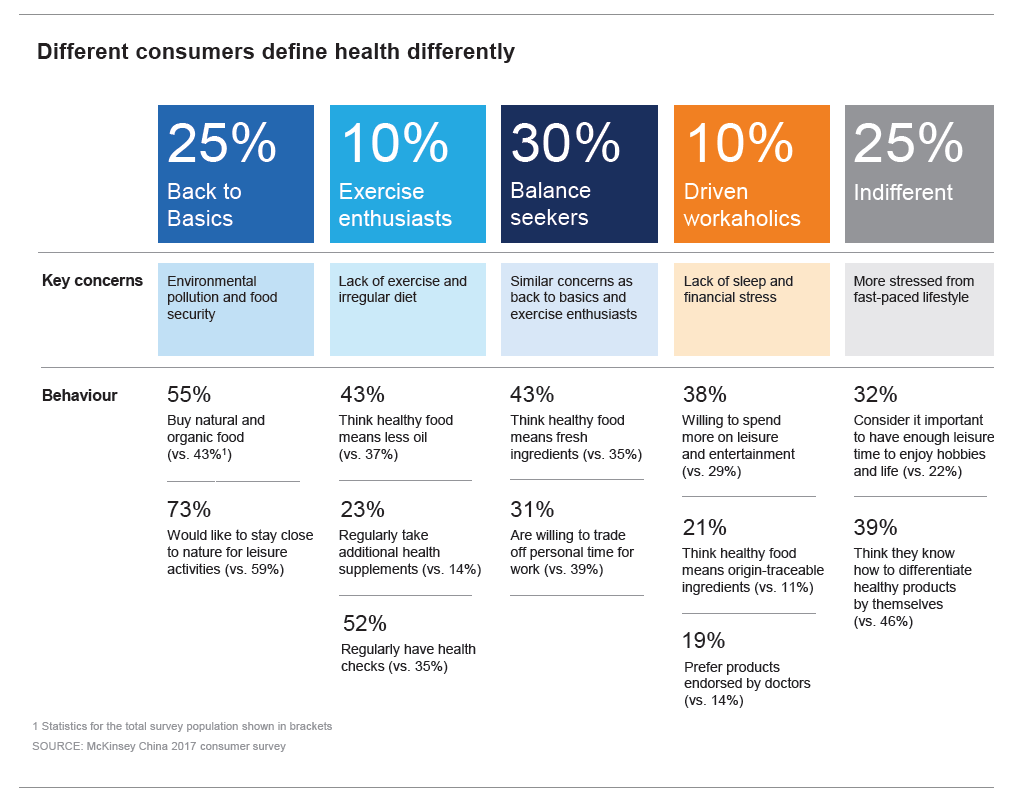

Of course, Chinese consumers don’t all share the same views toward health and we have identified five distinct segments of consumers based on their different attitudes toward health (Exhibit 1). Three segments, representing 65 percent of our respondents, are deeply concerned about this issue but express it in very different ways.

The “back to basics,” “balance seekers,” and the “exercise enthusiasts” will become more important and companies will need to create thoughtful messaging and marketing. Drilling down into the detailed nuances of this vast and complex consumer group is key to success.

Our research this year shed new light on one of the fastest-growing and increasingly influential segments of Chinese consumers—what we call the “post-90s” generation. While many reports in recent years have grouped China’s younger generation under the familiar term millennials, this term doesn’t fully capture the unique attributes of this segment of the population, which we define as people born between 1990 and 1999.

This generation exhibits very different behavior and attitudes not only with older generations of Chinese consumers but also the generation that we call the “post-80s,” which is generally lumped together with the post-90s generation in media reports that cover this topic. They also differ to Western millennials.

The post-90s generation grew up in a China unknown to their parents, one marked by extraordinary levels of wealth, exposure to Western culture, and access to new technologies. Comprising 16 percent of China’s population today, this consumer cohort is, by our projections, going to account for more than 20 percent of total consumption growth in China between now and 2030, higher than any other demographic segment.

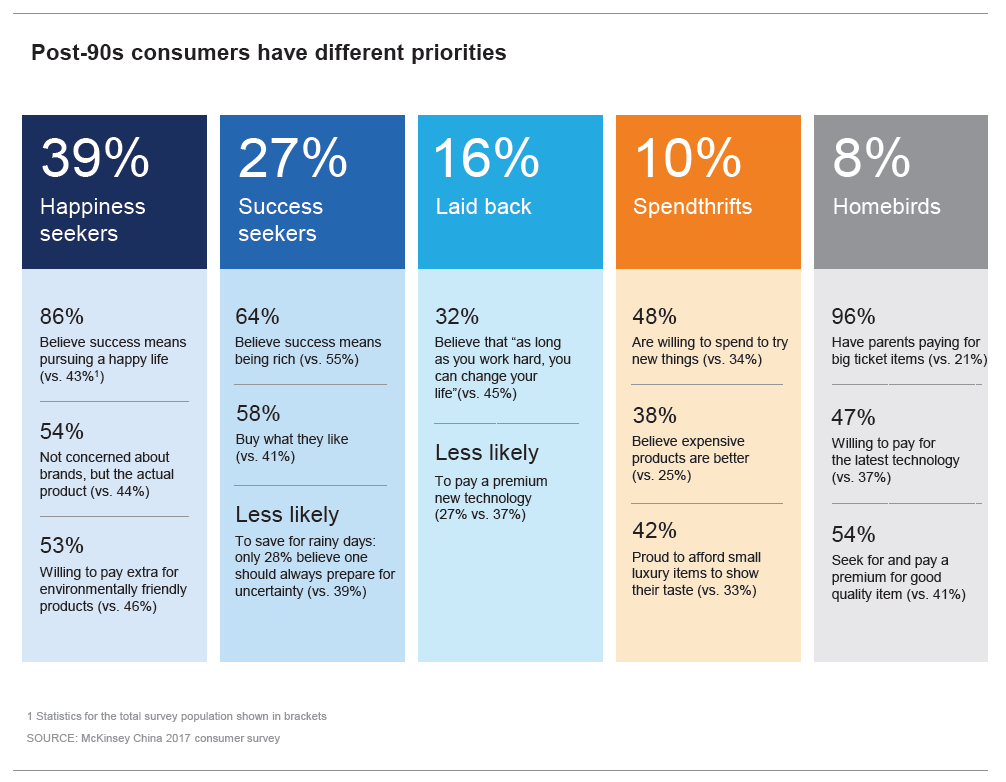

Asking them their attitudes toward certain areas of life—success, health, family, brands and products, and their future—yielded, in many cases, very different answers, which affects how they choose products and services. We sorted them into five distinct segments (Exhibit 2).

Each segment differs and all segments differ again from Western millennials. Companies that think carefully about their story and whether it will resonate with these segments based on their beliefs and attitudes will have an advantage.

In past surveys, we saw Chinese consumers take a strong interest in international brands. In other years, they acquired an interest in local brands. In recent years, they have developed a sharp eye for brands that deliver value for money.

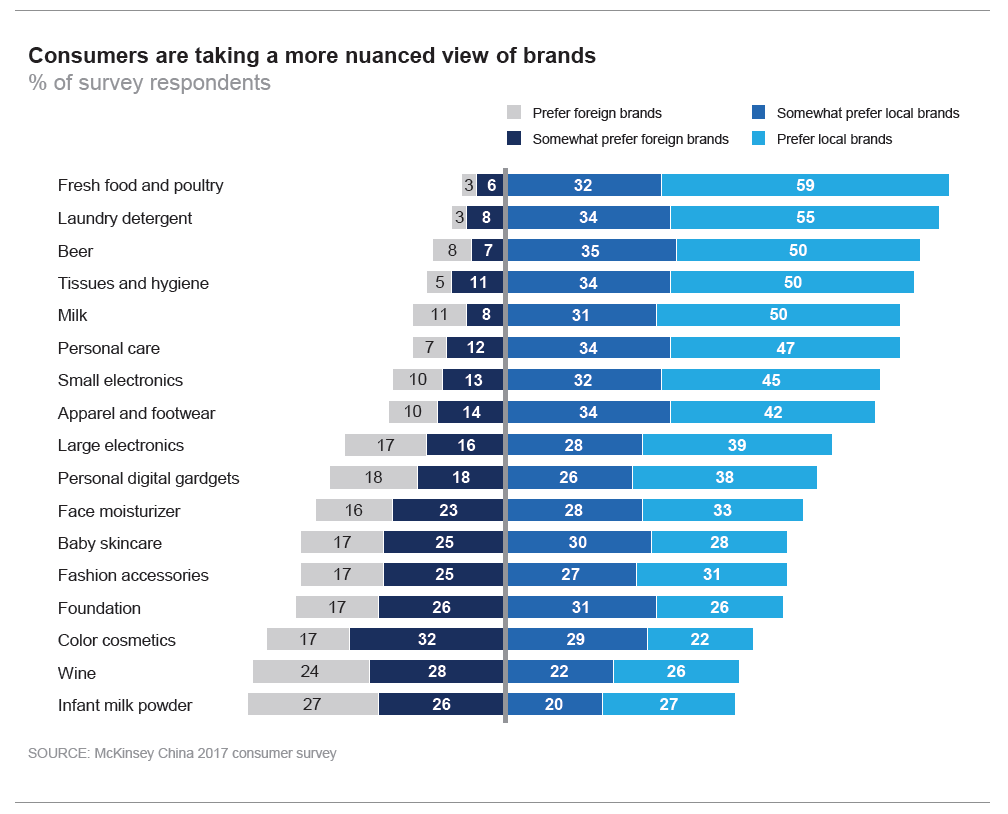

In this year’s survey, we’ve observed consumers taking a more nuanced view of the brands they choose.

Across the majority of categories surveyed, brand origin matters less than before. Consumers today have very clear expectations and they apply to local and foreign brands alike. First and foremost, they want value for money. That’s followed by quality products—they want their unique tastes catered to—and, lastly, they demand good aftersales service.

In 8 of the 17 categories surveyed, respondents showed clear preferences for local brands because they deliver in these three areas (Exhibit 3). Combined, these categories account for more than half of the total retail sales in China.

In many cases, Chinese brands have become credible competitors. This is especially true in the personal-digital-gadget and personal-care categories, where they have cemented their position over the last five years.

In 2012, Chinese brands accounted for 43 percent of the market in categories such as personal digital gadgets versus 63 percent in 2017. In personal care, Chinese brands made up 76 percent in 2017 compared with 61 percent in 2012.

Cost is less of a concern among today’s consumers, who appear to be preoccupied by quality. Huawei is a good example. The Chinese technology company is top of mind among consumers who are proud to own a Chinese smartphone that is as attractive and technologically advanced but less expensive than an iPhone.

In the remaining six categories, there is no clear preference for foreign or local brands. However, in the instances where foreign brands are preferred—namely cosmetics, wine, and infant milk powder—demand for better-quality and well-known brands emerged as the key factors in consumer decision making.

Across these six categories, 64 percent said they would seek out and pay more for better-quality products that last longer while 46 percent would buy internationally branded products if they had more money. More than half believe well-known brands are always of better quality (see sidebar “Brands beyond borders”).

However, as with the health-conscious consumers described earlier, a mismatch exists between perception and reality when it comes to brand selection.

Many believe that global brands with a longstanding presence in China, such as Olay and Bioré, are local brands. On the other hand, Chinese brands that have packaged themselves as international are often mistaken as foreign. Both foreign and local brands have opportunities to grow in China providing they can appeal to the increasingly nuanced needs of consumers.

There is no longer a single, one-size-fits-all definition of the Chinese consumer. These increasingly discerning shoppers are younger, healthier, and more brand savvy than ever, and they demand more from the products and services they buy. Both global and local companies must understand these nuances if they hope to craft brand and product messages that appeal to them.

Download “Double-clicking on the Chinese consumer,” the full report on which this article is based (PDF—3MB).

Wouter Baan is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Beijing office. Lan Luan is an associate partner in the Shanghai office, where Felix Poh is a partner and Daniel Zipser is a senior partner.

The authors would like to thank Lois Bennett, Corey Chen, Tong CT Chen, Wendy Chen, Rachel Jin, Glenn Leibowitz, Peter Li, Cherie Zhang, and Constance Zhu for their contributions to this article